The Louvre Museum in Paris is an architectural marvel, a palace built upon, renovated, and expanded from its origins as a fortress. Even awe would be an understatement to describe the feeling exploring its vast wings, its incredible Pyramide du Louvre, not to mention the most epic collection of artwork on display in the world. The first time I visited, I got completely lost, in part, because it’s one of the world’s largest museums at over 652,000 square feet. In between trying to track down the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo, and the Egyptian antiquities, my legs gave out after a half a day of hapless wandering.

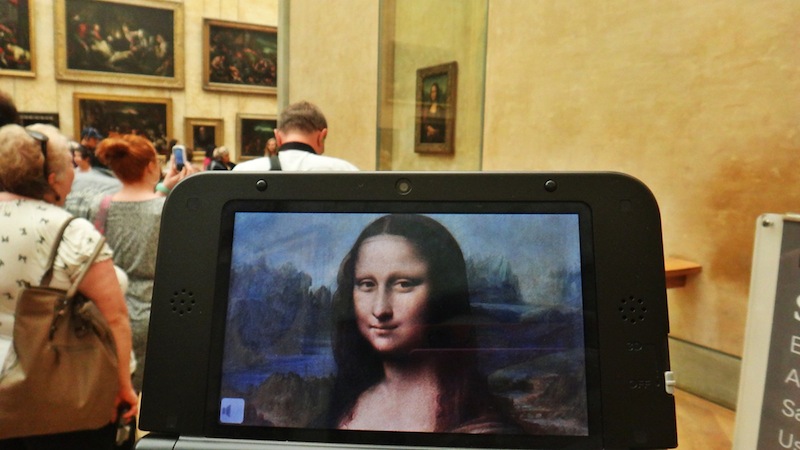

The second time I visited (which was almost ten years later), I had a much better experience, knowing exactly where I wanted to go, even getting a good grasp of its layout. This wasn’t the result of having learned my way around during my first visit, but rather because I had the official Nintendo DS Louvre Guide to lead me, complete with a GPS and 3D Imaging designed specifically for the museum (on rent for just five Euros at any of the booths).

My perceptions were more attuned with gaming than I’d realized, where spatial relationships in the real world were more intuitive rendered through the map on the 3DS. The Whorfian Hypothesis on cognitive development describes how language shapes our perceptions. Whether subconscious or not, I was relating to the visual language of gaming in a way that was surprisingly familiar, particularly in terms of the way I interfaced with the museum. The 3DS Guide made my experience not only more manageable, but (and I feel a little silly saying this in retrospect) it made the whole Louvre resemble a Zeldaesque labyrinth ready to be explored.

A couple years back, there was all the hoopla from critics stating that gaming could never be considered art. Even if I found the statement uninformed—all it took was just a peek at some of the galleries of concept art behind the games I’d worked on to convince me otherwise, not to mention the talented artists behind them—the incorporation of a game into the Louvre experience was especially surprising as I considered it a cultural bastion impervious to the sway of gaming. When I first saw tourists carrying the 3DS around the museum, a part of me felt annoyed that they couldn’t put away their gaming console for one day (‘What’d you do and see at the Louvre?’ ‘I leveled up my The World Ends With You character.’). When I found out its actual purpose, not only was I intrigued, but it got me thinking about my own prejudices about what the traditional museum experience entailed.

As the official guide of the Louvre, the “game” contains more than 600 photographs, 30+ hours of audio commentary, and “high resolution images, 3D models and video commentaries” about the artwork. That means you can zoom in on the details of the paintings, the digital magnifying glass focusing on background images via your screen. You can rotate and spin around sculptures from different angles (like above), all to the tune of a narrator informing you of a work’s history, significance, and interesting trivia. Rather than clash or even supplant the artwork, the 3DS increased my appreciation, visually pointing out specific approaches employed by the artist I would never have known about otherwise. The option to analyze or maximize any painting is invaluable, particularly on the large-scale images. You can search out favorite pieces and mark them on your map, which will then show you the quickest way there. It’s convenient being able to track your position on the 3D map and plan out your entire journey, especially because of how huge the grounds are.

There are limitations to the game; it doesn’t cover every exhibit, though they incorporate software updates as well as analyze user data and give feedback to the museum they can use to optimize and improve future visits. It also doesn’t take questions, and while it comes in several different languages, it lacks a Mandarin version, a feature many of my acquaintances bemoaned. Finally, the GPS isn’t perfect, and from time to time, it’ll get confused about your next destination.

These complaints are rather trivial considering it’s still far more convenient than any app, audio tour, and paper map I’ve used at other museums because of the way the 3DS integrates audio, visual, and tactile control into one package. It’s as close to getting a human guide as you can get without actually having one, but with the added benefit that you can travel at your own leisure, go off the beaten path, and stay in one location for as long or as briefly as you want. I’ve often felt like a herded sheep in tour groups, hitting bullet points on an unseen list, rather than being able to explore the more obscure and stranger pieces on display.

As I’ve mentioned, the Louvre is massive, and it’s both awe-inspiring and overwhelming being surrounded by masterpieces like Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People or David’s Coronation of Napoleon. The collection never seems to end and I felt like I could have spent a week there and still not appreciated more than a quarter of it. Many castles, just by their grand nature, are designed to make you feel insignificant, particularly in this instance. You’re in the presence of the king. Kneel, fool.

The 3DS was an equalizer and it felt like I was wielding my own personal tricorder (all it needed was a sensor beam). It helped tabulate the enormous gallery so that I could focus on the works on display, from the profound to the more playful.

I can’t think of anyone better to have created the Louvre Guide than Nintendo, the makers of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Ocarina was my first real introduction to an immersive 3D environment (even more so than Super Mario Bros. 64 and Crash Bandicoot on the PlayStation) and a huge part of that was because of the way it naturally adapted the 2D sprites I’d grown up with into a space that was not only traversable, but became as important a character as the main protagonist. The world was a puzzle to be unraveled and the additional dimension breathed an authenticity into the architecture that holds up to this day. The Deku Tree level was a revelation for me, and gaming space was changed irreversibly once I’d finished. I’ve heard stories about Shigeru Miyamoto’s intuitive grasp of camera and player controls, his dedication to perfecting the user experience.

For me, art is platform agnostic and can find expression in any medium, as long as it gives me a different understanding of the world, independent of whether I agree or disagree. Art in gaming isn’t just limited to the visual, but includes gameplay, design, and sound as well, all working in conjunction to create a unique experience. I still remember the sense of wonder at the Deku Tree level as I uncovered each of its secrets, all the way to the climactic plunge which was the coda to a brilliant level. In the same way, the 3DS creates a sense that each work in the Louvre is a puzzle, exhibitions with unique origins where even a dash of paint or a hint of a smile can have revolutionary implications based on the context in which it was created. This isn’t just art in a stuffy setting, only understood by the connoisseur, but something vibrant, exhilarating, and accessible. Ensconced in an interface familiar to gamers, the 3DS guide broadens the audience in a way that combines the favorite pastimes of the past with the present—as evidenced by many of the kids wielding their 3DS’s in front of classical paintings.

Nintendo’s creativity and consideration of the user experience in the 3DS Louvre Guide is what makes this seemingly quirky pairing work so well—so much so that a few weeks later, when I visited the Vatican Museum, I got lost, unable to find many of the exhibits I wanted to. I longed for a corresponding 3DS guide and found the accompanying audio tour primitive in comparison.

The only thing holding the experience back from being seamless was the fact that the 3DS was a separate object that I held and had to constantly refer back to.

This, of course, got me thinking about virtual reality and its significance for art. VR promises perfect immersion, but there’s also gear designed to augment reality. I tried out the Oculus Rift at Siggraph a few years back and even in its early stages, its potential for immersion held a ton of promise. With Microsoft, Sony, Valve, Google, and Facebook working on their own gear, each with their own distinct take, I couldn’t help but wonder specifically what it signified for the future of art. I’ve spent a lot of time playing with the Unreal engine, which is what some of these kits are using in their creation of their 3D worlds, and some of the better demos don’t just look indistinguishable from real life, but even more graphic. The duller palettes of actual cities seem muted in comparison to the vibrancy of art-directed worlds teeming with refractions, perfect sunsets, global illumination, and the complexity of a polygonal metropolis.

Will there one day be a virtual Louvre you can visit in your living room? Every work of art, every sculpture, even the hallways replicated with impeccable verisimilitude? No noisy tourists and no need to exhaust yourself finding a specific work of art (unless you wanted to). I realize it’s not the same as actually going (there are all the intangibles of traveling) and even in Star Trek, Captain Sisko wistfully notes that a holodeck baseball game isn’t a substitute for the real thing. I don’t want the virtual to replace the real and make the world a matrix-like MMORPG, and even if I did in other instances, that’s beyond the scope of this piece. What I’m more focused on is how a collaboration would work, the virtual gear functioning as an easel to paint even more fantastic landscapes than either could conceive of by themselves.

One practical example where this would have been very helpful is the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican Museum. It’s gorgeous, but hard to see from almost sixty feet below, even though Michelangelo intentionally used bright colors to make them more visible. I had a hard time enjoying my time there as I’d forgotten to bring my glasses and the chapel was packed to the brim with tourists, all pushing and tugging against each other. Imagine if you could use the virtual gear to zoom your view into the ceiling, visually gorging on the frescoes from below, swinging the camera around, actually seeing the stories in each character, the way they interconnect the Great Flood with the Garden of Eden and so on. Unlike a binocular, constrained to your location, this could actually let you see every detail up close. Goethe once said, “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what man is capable of achieving.” But the truth is, when we actually get there, the most we’ll see are general outlines that we try to decipher in the cacophony of the Biblical panoply.

I hope the 3DS Louvre Guide is a preview of the type of hybridization that will become more and more commonplace. The fusing of the real and unreal to create something innovative but familiar is going to change the artistic experience. Into what? That’s an exciting prospect to ponder.

While in Paris, I imbibed of some of Sartre’s work at a cafe (with a croissant and hot chocolate milk) and one of the passages that struck me were his musings on imagination and feeling:

“When the feeling is oriented toward something real, actually perceived, the thing, like a reflector, returns the light it has received from it. As a result of this continual interaction, the feeling is continually enriched at the same time as the object soaks up affective qualities. The feeling thus obtains its own particular depth and richness. The affective states follows the progress of attention, it develops with each new discovery of perception, it assimilates all the features of the object; as a result its development is unpredictable, since it is subordinate to the development of its real correlative, even while it remains spontaneous. At each moment perception overflows it and sustains it, and its density and depth come from its being confused with the perceived object; each affective quality is so deeply incorporated in the object that it is impossible to distinguish between what is felt and what is perceived. In the constitution of the unreal object, knowledge plays the role of perception; it is with it that the feeling is incorporated. Thus the unreal object emerges.”

I can’t wait to see what emerges in the years to come.

Peter Tieryas is a character artist who has worked on films like Guardians of the Galaxy, Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs 2, and Alice in Wonderland. His novel, Bald New World, was listed as one of Buzzfeed’s 15 Highly Anticipated Books as well as Publisher Weekly’s Best Science Fiction Books of Summer 2014. His writing has been published in places like Kotaku, Kyoto Journal, Tor.com, Electric Literature, Evergreen Review, and ZYZZYVA, and he tweets @TieryasXu.